By Stephen Guerriero

One of the greatest joys about teaching sixth grade Social Studies is being able to introduce my students to the world of Greek mythology. Many students have some idea of the Greek gods and heroes through popular YA fiction, like the books of Rick Riordan, but my classroom is a place where that mythology is contextualized and grounded in primary source material. For most students, the language and artistry of ancient text can be challenging, but I have an even more engaging way of having my students interact with Greek myth – visual imagery.

During the 5th century BC, the region of Attica around the city of Athens became famous for beautiful pottery vessels that were painted with scenes taken from Greek mythology. These vessels were either black-figure, in which black images were painted onto the natural terracotta red background of the pot, or red-figure, in which a black background was incised or designed to reveal red images. Both types of pottery were prestigious items, known all over the Mediterranean world for the skill of their makers. Attic pottery has been found all over Greece, throughout Southern Italy and Sicily, Spain, the Levant, and most voluminously in the Etruscan chamber tombs of Central Italy.

What I love about the imagery of Attic pottery is that an entire myth can be told in one or two scenes, leaving the viewer to fill in the details based on context clues. Because mythology was primarily composed as oral tradition, the stories of Greek gods and heroes were dynamic – there was no “right” version of a myth. A storyteller could add details, leave details out, emphasize a certain topic, or focus on a specific character. The general body of Greek myths were like a common language, the broad ideas known by all Greeks. The dynamism was a function of how storytellers told and retold narratives about known characters, events, and monsters. This is what we see on Attic vessels.

To illustrate this point, I share several descriptions of Cerberus, the guard-dog of the Underworld, with my students. Most are familiar with this creature having a single body and three vicious, barking heads. While that is the most widely known depiction of Cerberus, the 8th century BC poet Hesiod describes the dog as, “Cerberus, the savage, the bronze-barking dog of Hades, fifty-headed, and powerful, and without pity.” Students can compare that description with another ancient Greek writer known as Pseudo-Apollodorus, who said that, “Cerberus had three dog-heads, a serpent for a tail, and along his back the heads of all kinds of snakes.” Now, I like to add in a couple of works of visual art to help demonstrate that mythology and storytelling is as much a visual art as it is a textual one. The first is a 6th century BC plate from the Museum of Fine Arts here in Boston with a red-figure image that includes Hermes, Heracles, and Cerberus. In the scene, Cerberus is clearly seen with a single body and only two heads. The piece is especially interesting because it was made in Greece for an Etruscan funerary context. Might that have something to do with the artist’s choice to give Cerberus two heads? Or could it be easier than drawing three, or fifty for that matter? Or, like I ask my students, might the drawing be designed to make you think about multiple heads on Cerberus, while depicting only two?

The last piece I share with students in this exercise is a statue group depicting Hades, Persephone, and Cerberus. This one is even more fun because there’s so much going on in terms of storytelling. First, the statues of Persephone and Hades (Roman Pluto) demonstrate some traditionally Greek characteristics like their clothing, and Hades’s long beard. But they also have aspects of their connections to Hellenistic Egypt, like Hades wearing the “flower pot” shaped hat associated with the Egyptian god Serapis, and Persephone holds a type of rattle associated with the Egyptian goddess Isis. In fact, the most identifiable character is arguably that of Cerberus, who here is seen with his single body and triple heads.

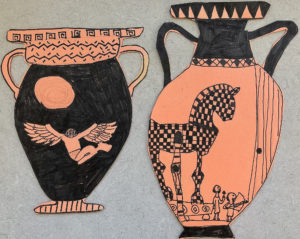

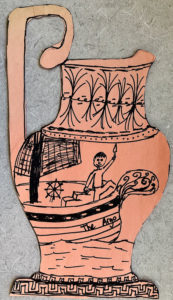

From our discussions, students are excited to then visually represent their myth storytelling in Attic pottery style. I use orange construction paper and Sharpie markers with students. They first read and see images of the myth they’re interested in drawing. Next, they sketch in pencil on their choice of vessel – I have templates for lots of different forms: krater, hydria, oinochoe, pixis, amphora, kantharos, plate, lekythos, and more. Finally, students share their work by turning our classroom into a museum gallery, while other classmates try to tell and retell the myths they see.

Here is a talk I gave to the Laurel Society of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. I explain how I use the artifacts in the Museum’s Greek and Roman collection to help students visualize Greek myth. Reposted here with permission from the MFA.